Diagnosis and Treatment of an MCL Injury

A trained clinician can diagnose many MCL injuries just by examining the knee, and getting in to see your physician as close to the time of injury as possible will make for a more accurate diagnosis. Physical assessments and aspects you’ll likely encounter include:

- Checking for tenderness directly along the ligament

- Assessing any swelling localized to the inner knee

- Range of motion measurements

- Watching for gait changes like limping or guarding the area

- Evaluating stability under a valgus stress test (pushing the knee inward)

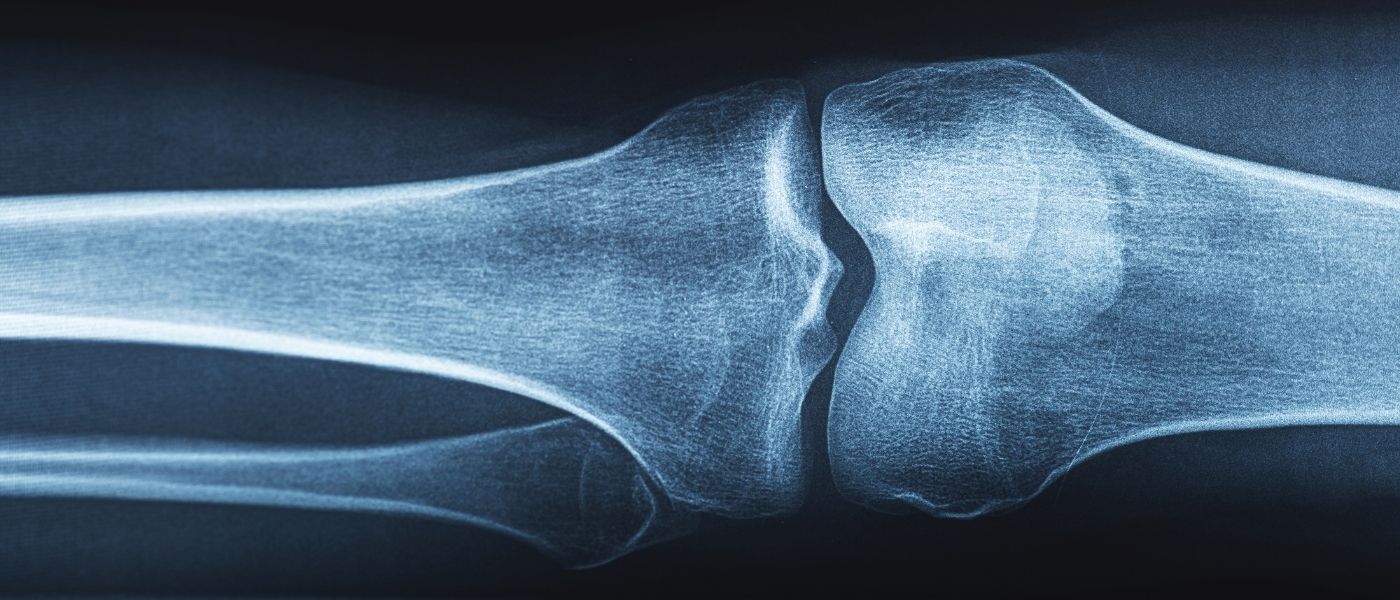

Imaging is used to rule out additional injuries or confirm severity:

- X-ray: rules out bone injuries, including small fractures. Sometimes it reveals an old MCL injury if a Pellegrini-Stieda lesion (MCL calcification) is present.

- MRI: the gold standard for viewing ligament tears and detecting associated injuries like ACL or meniscus damage.

- Ultrasound: a quick, low-cost option that can identify the injury in real time and identify inflammation.

One of the most reassuring things about the MCL is that it has a strong blood supply, which means it heals better than many other knee ligaments. Treatment of the injury depends on the grade.

Grade I is a mild strain that entails a slight stretch, microscopic tear, or minimal instability. Treatment is conservative and typically includes the RICE method, NSAIDs, short-term bracing, and/or early physical therapy focusing on quadriceps strengthening and gradual return to normal activity (usually 10 to 14 days).

Grade II involves more pain and swelling with mild to moderate looseness on valgus stress testing. Treatment is conservative in most cases, and might also include short-term use of a knee brace or immobilizer and/or progressively advancing physical therapy. The recovery timeline varies but is usually several weeks, and returning to normal activities or athletics requires demonstrating equal strength in both legs.

Grade III is a complete tear with significant laxity (looseness) and often occurs with other associated injuries to the ACL or meniscus. Treatment might still verge on conservative if it’s isolated, but surgery to repair or reconstruct using a graft might be recommended for athletes or when there is rotational instability or associated ligament injury. Rehabilitation for a grade III is more intrusive, and can include a hinged brace, early range-of-motion exercises, gradual progression to weight-bearing, and/or closed-chain strengthening exercises (keeping the foot planted). Full return to athletics or normal activities usually takes several months.