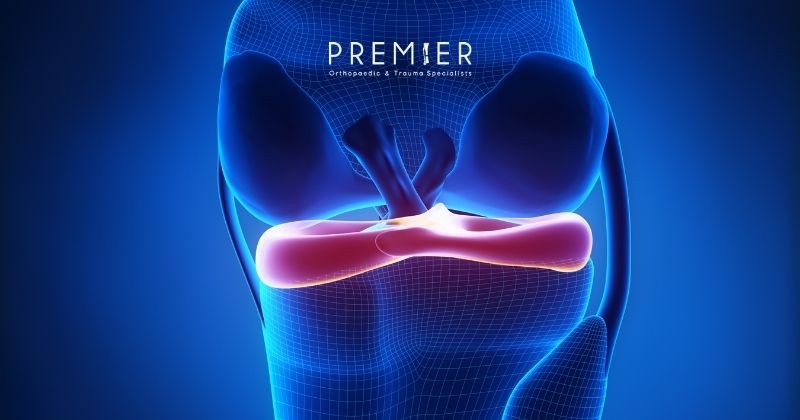

The knee is a busy neighborhood. It’s one of the most complex, high-traffic joints in the human body. It has to flex, extend, absorb force, stabilize the body, and bear several times our body weight with every step. That’s a tall order for a space made up of multiple moving parts.

We tend to think about “knee pain” as if it’s a single, simple problem, but…

Four bones meet here: the femur, tibia, fibula, and the patella. Tendons, such as the quadriceps and patellar tendons, connect muscles to bones and enable movement. Ligaments (the ACL, PCL, MCL, and LCL, MPFL, LPFL ) keep the joint stable. And surrounding all of this are tiny, anti-friction fluid-filled sacs called bursae.

It’s an intricate structure that keeps us moving, but it also creates opportunities for things to go wrong.

Despite the athletic nickname, one of the more common knee ailments, “jumper’s knee,” doesn’t just affect competitive jumpers.

What is Jumper’s Knee, Exactly?

“Jumper’s knee” is common vernacular for patellar tendinopathy, a condition where the patellar tendon (the dense, cordlike structure connecting the kneecap to the shin) becomes irritated, stressed, or structurally altered from repeated load-bearing, and it usually develops over time. It gets its name because it’s common in sports that involve explosive leg extension, in which the tendon has to lengthen while bearing force. Over time, that repetitive load can produce microtears and degeneration.

But the name is misleading. Patellar tendinopathy can (and very often does) develop in people who never set foot on a court.

Occupations involving repetitive motions that compress and put tension on the patellar tendon – floor installers, electricians, HVAC workers, plumbers, gardeners, carpenters – are common culprits. Anatomical differences are also a contributing factor – wide Q-angle (the angle between the hip and knee), maltracking of the patella, or a patella that sits unusually high or low can all shift the mechanical load onto the tendon. Tight quads, hamstrings, calves, or hip flexors increase tension as well.

There’s also foot and ankle alignment that adds another layer. Flat feet, overpronation, or unstable ankles can redirect force upward, and overload the patellar tendon with each step or squat. Beyond structural malalignment, systemic health conditions like diabetes, inflammatory autoimmune diseases, kidney disease, obesity, and metabolic dysfunction compound tendinopathy by impairing blood flow and tissue repair necessary for tendon recovery. It’s not an “athlete’s problem,” it’s a load and recovery problem.

If the tendon receives more force, causing injury faster than it can remodel and repair, its collagen fibers begin to break down. This chronic degeneration is known as tendinosis. Contrary to popular belief, many chronic cases contain very little inflammation – patellar tendinopathy often shows degenerative, not inflammatory, changes under the microscope.1

Symptoms are a reflection of mechanical overload. Pain usually appears below the patella, especially after jumping, climbing stairs, running downhill, squatting, or even rising from a chair. Some people notice the “movie theatre sign” – an ache that builds during prolonged sitting with the knees bent. And it follows a signature pattern: pain increases with load, and often lessens or stops when the load stops.

While the condition centers on the patellar tendon, its symptoms can overlap with bursitis.

Bursitis and Tendonitis 101

The bursae are tiny, fluid-filled sacs that cushion the joint spaces, and the knee contains several to reduce friction between bones, tendons, and soft tissues. When they become irritated, inflamed, or overloaded, it’s called bursitis, a condition that can mimic or compound jumper’s knee.

Because these bursae sit adjacent to the patellar tendon, it’s extremely common for bursitis and patellar tendinopathy to occur together. A person may feel a diffused ache or swelling from bursitis while also experiencing sharp, activity-related pain from tendon overload.

Tendonitis refers to short-term inflammation of a tendon, usually after a sudden increase in activity or an acute overload, and symptoms include warmth, swelling, and acute tenderness. But some cases traditionally labeled “tendonitis” are actually tendinosis, a chronic degeneration of the tendon’s collagen fibers with minimal inflammation. The distinction matters when it comes to treatment: anti-inflammatory strategies help tendonitis but do little for tendinosis, where the real solution is controlled, progressive strengthening.1 The terms get used interchangeably because both cause pain around the tendon, but medically and structurally, they are not the same injury.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Patellar tendinopathy and bursitis are best evaluated through a combination of medical history, physical examination, and targeted imaging. A skilled provider will examine the entire hip-knee-ankle chain, since dysfunction in one region often transfers abnormal load to another. Weak hip stabilizers, stiff ankles, or foot alignment issues can all change how force travels through the patellar tendon.

Ultrasound is commonly used for diagnosing tendinopathy because it allows real-time visualization of tendon thickness, fiber alignment, and vascular changes; it can also identify bursitis by showing excess fluid in the bursal sacs. Sometimes an X-ray is also employed to help rule out bone injuries or structural abnormalities, and MRI might be utilized for chronic cases, suspected partial tears, or when planning surgical intervention.

The first phase of treatment usually entails calming the symptoms. This might include the use of NSAIDs to reduce inflammation, if present, or modifying activities, though it isn’t always necessary to stop movement entirely.

Physical therapy is a front-line course of action for jumper’s knee. With controlled movements, eccentric strengthening (a type of exercise where the muscle elongates under load) stimulates the tendon to produce new, properly aligned collagen fibers, gradually strengthening the tissue. Therapists also address flexibility, especially in the quadriceps, hamstrings, calves, and hip flexors, since tightness in these muscle groups increases tension on the patellar tendon. Physicians will also monitor gait, and suggest hip and core strengthening to restore normal biomechanics, reducing strain on the knee during daily movement.

Tendons heal more gradually than muscles because they have less blood supply, so rehabilitation strategies are slow and progressive – it could take weeks, or even months. Hurried healing could cause symptoms to flare, and you might have to start over from square one.

Though rare, surgery becomes an option when conservative treatment fails (typically in cases involving partial tears or severe, long-standing tendinosis).

Avoiding activity isn’t the name of the game with jumper’s knee – healthy tendons and bursae depend on alignment, strength, circulation, and controlled loading. Our team of physical therapists at Premier Orthopaedic & Trauma Specialists are focused on restoring optimal movement mechanics and building resilience through evidence-based, personalized care. Whether you’re an athlete, a trades professional, or someone simply trying to return to daily life without pain, our team can help you heal fully, strengthen safely, and protect your knees for the long haul.

- Bass E. (2012). Tendinopathy: why the difference between tendinitis and tendinosis matters. International journal of therapeutic massage & bodywork, 5(1), 14–17. https://doi.org/10.3822/ijtmb.v5i1.153.